|

If you are a professional or a writer who is passionate about health, racial, and social equity, consider contributing to our blog! Visit our Volunteer page to learn more. |

|

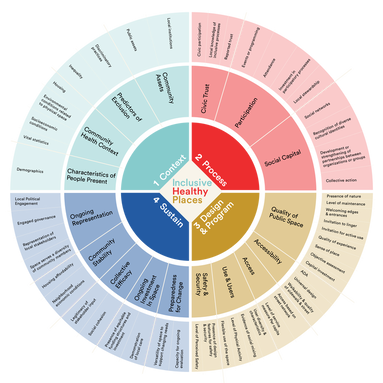

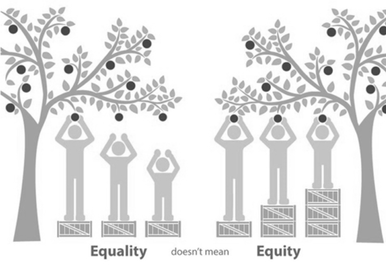

by Julia D. Day  Folkets Park in Copenhagen, Denmark Folkets Park in Copenhagen, Denmark If you're reading this blog, chances are you care deeply about achieving equitable outcomes. But how do you know if you're making progress? Working for health equity—defined as “all people having a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible” (1)—is necessary, but how do we know when we have created environments that foster equity? And how do we ensure that terms like equity and inclusion aren’t just flimsy buzzwords, or worse, used to “equity-wash” something that isn’t equitable at all? To address these concerns, Gehl (an urban research and design consulting firm) teamed up with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and colleagues at the former Gehl Institute, to create the Inclusive Healthy Places Framework, which defines principles and metrics to guide and evaluate public space projects that support health equity (2). The Framework aims to demonstrate that public realm is a key component of health equity, and to create a platform through which more cross-sector partnerships can develop. What this looks like in practice varies greatly and depends on local context. One example is Folkets Park in Copenhagen (see picture above). Located in one of the city’s most diverse neighborhoods, this small neighborhood park underwent a redesign led by Kenneth Balfelt, a visual artist and urban designer, that prioritized identifying all stakeholders who might use the park and deepen community engagement as a path to building trust, ownership, and ultimately, high rates of visits. The park attracts a cross-section of families, migrants, the unhoused, and the yuppie set, in part by providing a range of design features—such as a play structure for small and big kids, and zoned lighting so unhoused migrants can sleep and rest comfortably without fear of theft. Through engagement, the park was established as a place that should welcome multiple communities from the neighborhood (3). "Inclusion" and "health equity" mean different things based on context, audience, and one’s personal experience. The Framework does not outline a prescriptive way to work, but instead provides the tools practitioners can use to establish common ground across sectors and ensure inclusion is a driving and sustained component of their approach. Our role is to make space for these varied definitions to surface, to integrate them into our work, and to lift up their importance in developing projects and initiatives that people can embrace and trust. In the Framework, inclusion is presented as: An outcome: Everyone who uses a public space must feel like they belong, are respected, safe, and accommodated, regardless of who they are, where they come from, race, income, abilities, how old they are, or how they use a public space. A process: Inclusionary public space processes recognize and respect the needs and values of the people using the space, and the assets present in a place. These processes actively engage and cultivate trust among people, ultimately allowing all members of the community to shape, achieve, and sustain a common vision.  Inclusive Healthy Places Framework Inclusive Healthy Places Framework Drawing from recent research at the intersection of public health, equity, and the built environment, the Framework identifies the (158!) core drivers, indicators, and metrics of inclusive places and projects that can guide project development and measure impacts. You might be thinking: woah, 158 is too many for practitioners. We hear you. The intent is that practitioners will work with their partners and core stakeholders to select the metrics most relevant to their projects and goals, and focus on those. A goal of the Framework is to help practitioners develop a planning process that isn’t necessarily linear, but that incorporates a cycle of action, evaluation, and adaptation. The Framework is being applied to projects across the country. While each project is different—some focus on health and safety, some on creating inclusive parks, others on developing technical resources—each will use the Framework to: 1) Make public processes and outcomes more truly democratic and accessible 2) Value and validate lived experiences, and 3) Bridge difficult to navigate gaps across fields and interests The impact of these projects is being documented through stories and cases that hopefully will inspire further adaptation and use across the country, and engage a wider audience to do the real and challenging work of shaping more equitable outcomes. Stay tuned! Picture credits:

Folkets Park in Copenhagen, Denmark: Steven Johnson, Boundless The Four Principles: Inclusive Healthy Places Framework References 1. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. What is Health Equity? https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html. Published 2017. Accessed March 17, 2021. 2. Gehl. Inclusive Healthy Places Framework. https://gehlpeople.com/shopfront/inclusive-healthy-places/. Published 2016. Accessed March 17, 2021. 3. Meeting of the Minds. Planning Public Spaces to Drive Health Equity. https://meetingoftheminds.org/planning-public-spaces-to-drive-health-equity-27760. Published 2018. Accessed March 17, 2021. About the author Julia D. Day is Director and Team Lead at Gehl, NY. She develops projects across design, policy, and strategy, focusing on creating public spaces where people can engage with, and shape their cities. With Gehl, Julia develops multi-sector partnerships that highlight the power of place to impact health and wellbeing and make people visible in the city-making process, and manages the Gehl NY team. Julia is a member of the Advisory Council of Health Equity Initiative (HEI) since 2019 and has participated as a speaker or facilitator in HEI events since 2016.

2 Comments

10/27/2023 01:23:52 am

What is the DGCustomerFirst.com survey?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2023

CategoriesEditors:

Renata Schiavo, PhD, MA, CCL Alka Mansukhani, PhD, MS Radhika Ramesh, MA Guest posts are by invitation only. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed