|

If you are a professional or a writer who is passionate about health, racial, and social equity, consider contributing to our blog! Visit our Volunteer page to learn more. |

|

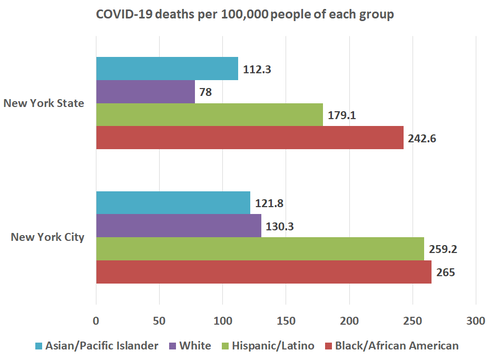

by Upal Basu Roy, PhD, MPH  It has been literally just about two months since I developed that fateful cough and slight breathlessness barely a month since COVID-19 had entered public health vocabulary. COVID-19 (short for Coronavirus disease-19) is caused by SARS-CoV-2, a type of virus that belongs to the same family of viruses that cause SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome). The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, reinforcing the contagiousness of this viral disease (1). As public health practitioners, we understand the severity of a viral pandemic that can have devastating consequences on the population. As of today, COVID-19 cases have been detected in all continents except Antarctica. I live in New York City, one of the first epicenters of the disease in the United States. One may automatically assume that NYC is adequately equipped to handle a pandemic the magnitude of COVID-19. I was incredibly lucky to have recuperated from COVID-19 without the need for hospitalization. But that does not stop me from reflecting on the glaring health disparities that COVID-19 has exposed in our community. While this is nothing new to public health practitioners such as myself, let us not underestimate the fact that COVID-19 has only amplified the many health inequities that already plague marginalized racial and ethnic communities in the United States. In other words, these inequities already existed! The pandemic merely exposed them. The CDC notes that racial and ethnic minorities are especially vulnerable, given their living situations (such as residential segregation), work conditions (much lower likelihood of having the option to work from home), higher prevalence of chronic health conditions, and lower access to healthcare (2). Statistics from both NYC and New York State attest to this fact. African Americans are three times more likely to die from COVID-19 in New York State as compared to Whites (3), and twice more likely to die from COVID-19 in NYC as compared to white community members (4). Similar disparities exist for Hispanic community members as well.

And while I discuss New York State, I would be remiss in not mentioning that it is not just marginalized racial and ethnic populations that have inequitable access to care. Take for example, Sullivan County—a county close to New York City and designated as a non-metro area. Sullivan County has had 991 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people, numbers that starkly resemble the 1197 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people in NYC (5). The big difference lies in how well-equipped the two areas are. NYC has 66 hospitals across the five boroughs, while Sullivan County has only two (6). The higher density of elderly population with co-morbid conditions in non-metro areas makes these areas especially vulnerable to a COVID-19 outbreak (5). The pandemic is exposing another health disparity that has always existed—the rural-urban healthcare divide. So, what can you do to bridge these gaps?

Every effort towards mitigating the devastating effects of this pandemic counts—even more so for already underserved communities. Picture credit: www.pixabay.com References: 1) Ducharme J. World Health Organization Declares COVID-19 a 'Pandemic.' Here's What That Means. https://time.com/5791661/who-coronavirus-pandemic-declaration/. Published 2020. Accessed May 8, 2020. 2) CDC. COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. COVID-19 Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html. Published 2020. Accessed May 10, 2020. 3) APM. The Color of Coronavirus: Covid-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. (Updated May 20, 2020). https://www.apmresearchlab.org/covid/deaths-by-race?rq=COVID-19. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020. 4) NYCDOHMH. Rates of Cases, Hospitalizations and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-05142020-1.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020. 5) Fehr R, Kates J, Cox C, Michaid J. COVID-19 in Rural America - Is There Cause for Concern? https://www.kff.org/other/issue-brief/covid-19-in-rural-america-is-there-cause-for-concern/. Published 2020. Accessed May 8, 2020. 6) NYSDOH. Hospitals by Region/County and Service. https://profiles.health.ny.gov/hospital/county_or_region. Published 2020. Accessed May 10, 2020. 7) Peterson A. This Pandemic Is Not Your Vacation. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/annehelenpetersen/coronavirus-covid-cities-second-homes-rural-small-towns. Published 2020. Accessed May 8, 2020. About the Author: Upal Basu Roy, PhD, MPH, serves on the Board of Directors of Health Equity Initiative since 2015, and more recently as the Board’s Co-Vice President. Upal is the Vice President of Research at LUNGevity Foundation. In his current role, Upal oversees LUNGevity’s research awards program and manages LUNGevity’s patient-focused research center. Upal is passionate about eliminating health disparities and increasing access to cancer care. Read Upal’s full bio here.

1 Comment

9/10/2023 07:22:43 am

Hello Canada! Loblaws provides a survey for their customer's feedback and at a time, improving their services. In the part of the survey, Loblaws gives the best chance to the survey winners by taking the survey at https://storeopinion-can.com/ get a chance to win a $1000 Optimum PC gift card.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2023

CategoriesEditors:

Renata Schiavo, PhD, MA, CCL Alka Mansukhani, PhD, MS Radhika Ramesh, MA Guest posts are by invitation only. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed