|

If you are a professional or a writer who is passionate about health, racial, and social equity, consider contributing to our blog! Visit our Volunteer page to learn more. |

|

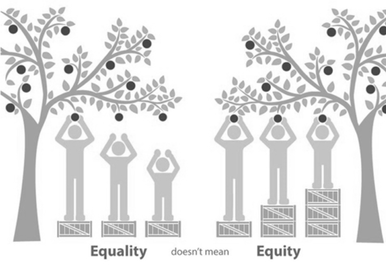

by Bree Bode, Karah Brink, Adriana Akers, Josh Leffingwell, Michelle Davis  Urban design is a critical concept for supporting the infrastructure and well-being of a city, catalyzing a higher quality of life, and optimizing equitable built environments (1,2). When constructs of urban design are paired with human design frameworks, approaches, practices, and principles, the potential to positively shift the social and political factors of health (SPFOH) in an equitable manner is more attainable (3,4). Without such frameworks, approaches, and inclusive practices, the concepts of urban design negatively impact people globally. When urban design has been paired with motives of xenophobia, racism, or gender bias, the comprehensive SPFOH have compromised livelihoods as seen in historical and recent examples in both the United States and Europe (5-7). In Detroit, Michigan, a real estate developer built a six-foot high concrete wall known as “The 8 Mile Wall” or “The Wailing Wall” (5) which gravely impacted Black Detroiters’ accessibility to certain parts of the city and blocked the flow of economic capital into their community (5). These racial segregation practices were also prolific in New York which forced Black residents into specific communities, including Brooklyn, New York (6). In Denmark, during 2018, the Danish government passed a “No Ghettos” law which aims to reduce the number of “non-Westerners”, namely people of color and Muslims, in social housing to 30% in ten years. Driven by assimilationist policies and xenophobia, the “No Ghettos” law allowed the forced displacement of families as the government cited a “need” to diminish the percentage of people with an immigration background who live in a single neighborhood (7). Doan, P. (2007) outlined how urban design can impact the perception of safety among people in the transgender community, and documented experiences of violence as a catalyst which compromised social spaces and dwelling spaces (8,9). Doan's findings coupled with Hopkins’ (2020) findings highlight the need for safer spaces within urban areas; namely, on public transit, at times of natural disasters, and in neighborhood level tracts (8,9). As seen in these examples, the seed of implicit bias can develop into explicit bias as a lack of human-centered design informs the SPFOH. Historically, policies and systems have placed wealth over health, catalyzing inequities. However, there are urban design solutions that are promoting hope and equity.

How can urban planners help? Urban planners can adopt frameworks, approaches, or practices such as the following to promote equity: 1) 10 Essential Public Health Services (10), 2) Community First Development (11), 3) Gender Inclusive Urban Planning Design(12), 4) Community Development Framework (13), 5) and/or The Inclusive Healthy Places Framework (14) (IHPF) into strategic urban planning efforts. Such frameworks, approaches, practices, and principles have similar characteristics and are grounded in community empowerment, human rights, inclusion, social justice, self-determination and collective action which shape our work in community health, and should be adopted in urban design (4). The 10 Essential Public Health Services provides a public health framework for the pursuit of health for all communities, and the removal of any barriers to positive health outcomes (10). The Community First Development approach initiates community change only after a community member or group of community members presents the project details (11). Practices of Gender Inclusive Urban Planning Design aims to bring the conversation about gender equality into each step of the urban design planning process (12). The Community Development Framework (CDF) by the Coalition of Community Health and Resources Centres of Ottawa, Canada, is defined “as a way to develop community that focuses on neighborhoods. It brings together residents, community organizations, funders, researchers, and city services to build strong neighbourhoods (1).” The IHPF, developed by Gehl and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is a data-driven tool for communities, planners, designers, and policymakers that describes the factors that should be considered in the planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of public spaces (14). Gehl and RWJF point out that urban planners need to keep in mind particular principles linked to research on health, equity, and place to successfully adopt the IHFP. The first principle (13) is community context – required action step, study existing conditions and lived experiences before beginning to ideate on a project. This can mean mapping the demographic groups who live in the vicinity of a project, taking time to understand and acknowledge the state of inequality and the level of discriminatory practices that present in a place, and evaluating the existing community health context. The second principle is process – required action step, practice action-oriented community engagement to promote civic trust, participation, and social capital by engaging residents. This principle calls urban planners to make the process of inclusion a central input to the place-shaping process. The third principle, design and program principle - required action step, identify the physical characteristics that promote inclusivity and health in a place—like the presence of nature, walkable sidewalks, welcoming edges and entrances, invitations to linger, and invitations for active use. Finally, the fourth principle, sustain principle, required action step, monitor to discern if inclusion and health has been maintained in public spaces and the communities that they serve, over time after a project opens (13). Urban planners can also help by make equity commonplace in urban design and document the multi-dimensional assets of the community members. First, using a human-centered urban design approach, listening and observing should be implemented since communities, especially diverse communities, have ideas both big and small that are valuable and necessarily diverse. To get the most out of the listening process, planners and developers can benefit from embracing empathy, viewing community members as experts, and using motivational interviewing techniques. When speaking, using plain language is vital. We need our planners and developers to understand that empathy is not only “walking in someone’s shoes”, but instead is believing and acknowledging the lived experiences of others. The experiences of community members have shaped their views of their surroundings, and it shapes the way they walk in a space. We need to move through their spaces not with preconceptions of what needs to happen, but instead to start from a place of learning, a place of trust-building, and then a place of action. What can communities do? “Share”. While it might not be easy to share thoughts and emotions due to experiences that have cause disproportionate impact, community members can try to speak their ideas as “sharing” is the gateway to equitable urban design. There are multiple meanings behind that word “share”—1) sharing one’s geographical space with others and 2) sharing a vision for that community space. Planners and developers need to hear community members’ voices and understand their vision. So, create a vision for the space that is positive and has the future of self, others, and the collection of various communities in mind. Cities are not built for individuals; they are built for a collection of communities. Do not write off the goals or dreams of others, but instead think inclusively. Neighbors tend to band together to exclude others—college students, renters, commuters, or the like; these people are part of the community as well. Share community spaces with the collective and learn to walk alongside them. We have a long way to go in achieving global health equity. Addressing the policies, systems, environments, behaviors shaped in bias and the associated social discrimination of race, gender, age, belief systems, etc. requires intentional change in the policies, systems, and processes which have historically determined urban design. One important method to achieve equity is to disrupt the historical practices of urban design and move towards an equity-based method of urban design. Picture credit: https://www.shutterstock.com/image-vector/city-development-people-engaging-activities-building-618241412 References 1) Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council (ASBEC) (2015) ‘What is Urban Design?’ https://urbandesign.org.au/what-is-urban-design/. Accessed July 18, 2021. 2) United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2020) ‘Basic Information about the Built Environment.’ https://www.epa.gov/smm/basic-information-about-built-environment. Accessed July 18, 2021. 3) DC Design (2017) ‘What Is Human-Centered Design?’ https://medium.com/dc-design/what-is-human -centered-design-6711c09e2779. Accessed July 18, 2021. 4) Public Health Association Australia (2018) ‘What are the Determinants of Health?’ https://www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/2756. Accessed July 18, 2021 5) Lee, A. (2020) ‘Heard of The Eight Mile Wall? Unearthing its History of Segregation in Detroit’. Detroit Is It. https://detroitisit.com/the-eight-mile-wall/. Accessed June 24, 2021. 6) Chronopoulos, T. (2020)’“What’s Happened to the People?” Gentrification and Racial Segregation in Brooklyn.’ Journal of African American Studies 24, p. 549–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-020-09499-y7 . 7) Burnett, S. (2021) ‘Why Denmark is Clamping Down on 'non-Western' Residents’. DW. https://www.dw.com/en/why-denmark-is-clamping-down-on-non-western-residents/a-56960799. Accessed July 7, 2021. 8) Doan, P. L. (2007). Queers in the American City: Transgendered perceptions of urban space. Gender, Place & Culture, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/09663690601122309 9) Hopkins, P. (2020). Social Geography II: Islamophobia, transphobia, and sizism. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519833472 10) Centers for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) (2021) ‘10 Essential Public Health Services’ https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html Accessed July 10, 2021 11) Community First Development (2021) ‘Our Approach’. https://www.communityfirstdevelopment.org.au/approach. Accessed July 10, 2021 12) Terraza, H. et. al. (2021) ‘Handbook for Gender-Inclusive Urban Planning and Design’. The World Bank. https://olc.worldbank.org/system/files/145305ov.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2021 13) Coalition of Community Health and Resource Centres of Ottawa (2021) ‘Community Development Framework’. http://www.coalitionottawa.ca/en /a/community-development/community-development-framework.aspx. Accessed July 7, 2021 14) GEHL (n.d.) ‘Inclusive Healthy Places Framework’. https://gehlinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/IHP_Framework-Summary.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2021 About the authors Bree Bode (she/her) advocates for better policies, systems, and environments to promote optimal health and well-being. A PhD Candidate at Wayne State University and a Nutrition Program Coordinator with Pediatric Public Health Initiative at Michigan State University Bree is curious about the intersection of food insecurity and obesity. Bree is co-chair of Health Equity Initiative's Volunteer Member Professional Development Committee. Read Bree's full bio. Karah Brink (she/her) holds a master’s in Social Policy for Development from Erasmus University Rotterdam and a bachelor’s in Psychology from Spring Arbor University. Her areas of passion include implementing decolonial practices into development work, food sovereignty, gender equality, and care for the earth. Adriana Akers (she/her) holds a master’s in city planning, a Certificate in Urban Design from MIT and has worked on urban projects in over ten countries. At Gehl, Adriana focuses on creating places that are equitable, exciting, comfortable, and great for walking, biking, and spending time in public spaces. Josh Leffingwell (he/him) is a Partner and Founder of Well Design Studio. Josh has served in multiple roles to promote community voice and participation for the betterment of cohesive cities such as a Commissioner on MobileGR, Co-Chair of East Hills Council of Neighbors, and Vice Chair of the Vital Streets Oversight Commission. Michelle S. Davis (she/her) currently serves as Senior Advisor for Public Health Strategy within the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. She provides leadership on cultural competency, diversity, equity and inclusion and readiness of federal employees to respond to natural and man-made disasters. Michelle chairs HEI Advisory Council. Read Michelle's full bio.

7 Comments

Jody Bode

8/16/2021 08:59:23 am

Well written and thought provoking.

Reply

6/15/2022 09:14:41 am

It makes sense that planning out an urban area would be difficult. I can see how the right expertise for that would be really beneficial. I can see how getting a town planner would be important.

Reply

10/31/2022 02:37:37 am

Thank you for highlighting that the principles of urban planning have a harmful influence on people all over the world without such frameworks, methodologies, and inclusive practices. My father purchased a home in a mountainous area with a fragile ecosystem. To avoid having a harmful impact on people and the environment, I shall advise my father to see a town planning specialist.

Reply

4/17/2023 05:04:55 am

Nice and informative paragraphs and articles thanks for sharing this site…

Reply

5/31/2023 03:53:58 pm

This article highlights the significant impact of urban design on health equity and the consequences of bias within urban planning. It sheds light on historical examples of racial segregation and discriminatory practices, emphasizing the need for inclusive and community-driven approaches. By promoting human-centered design principles and addressing implicit biases, we can strive for more equitable built environments that prioritize the well-being of all residents. It is crucial to learn from past mistakes and embrace urban design solutions that foster hope and promote equity for everyone.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2023

CategoriesEditors:

Renata Schiavo, PhD, MA, CCL Alka Mansukhani, PhD, MS Radhika Ramesh, MA Guest posts are by invitation only. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed